C. Halberstadt Bender Ryan

and Her Gynecologist

By Kelly Levan

“Never underestimate the power of fear.” – Patricia Catherine Nixon

Ely, Nevada, 1912.

God created the world in his image, but only the hummingbird is beautiful. From my exposed position on the table, I could see the Rufous outside the window glass, sucking hard at an Indian Paint Brush, wings furious. His orange gorget flashing like fish scales. I hated hummingbirds.

“It’s the hysteria,” Dr. Duggan said, nodding his tiny lucid head.

Gynecologists never recognize prophecy. I shouldn’t have come to him.

“The hysteria!” I said. I’d heard about it happening to other women in Ely. In my head I could hear them repeating the word to their doctors, one after another, an echo of diagnoses. Chime-like. Pretty, as their doctors’ words weren’t. “But Doctor, I’m going to die in thirteen years. I had a, a revelation.”

“Thirteen years—Kate my dear, I’m a Catholic and a doctor, most of the time in that order, and as such I believe that if you’re right, well, it sure would be an unfortunate coincidence.” He chuckled. “You’re a girl of strong faith. You should know better. Thirteen years.” He wobbled over to his white cupboards and somehow squatted to open the bottom left door. He removed a cat-sized machine wrapped in a long electric cord.

“You’ve been suffering low spirits, forgetfulness, general soreness and irritability—right? Irritability?”

“I suppose.”

“I thought so. Now, these coupled with the fainting spell you had a week after little Thelma’s birth, well—”

“Not Thelma,” I said.

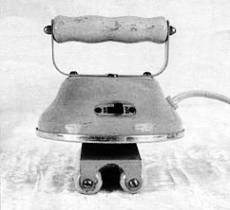

“Hmm? Not Thelma?” The machine looked like a toaster—My friend Alma just bought a toaster, I thought needlessly—but with a handle sticking out where the toast would pop up. And wheels.

“Bill likes that we call her Pat, since she was born on St. Paddy’s Day.”

“Oh, I see,” he nodded, understanding. “That so? I could have sworn it was the day prior. Anyhow, the hysteria’s typical after a birthing: A woman becomes tense, scared even, about her family’s future, and her own future. And it’s not unheard of for the patient to have what you called ‘visions,’ when she’s in this kind of a state.” Typical. Typical. My mind

“It wasn’t really a vision,” I said quietly. It wasn’t, more to the point, visual.

He plugged the device into the wall beside the table and held it up over my knees. “Now, don’t be nervous, dear. They use this all around the country, even in Arizona and New Mexico. It may seem strange and new-fangled to us in our backwards mining communities, but in the cities, it’s as common as—well, as the hysteria.” He chuckled again. “We doctors aren’t too good with metaphors. Ah, but we can’t go inviting poets into the examining rooms, now can we?” He smiled and tapped on my right knee. I heard trumpets. “I’ll need you to open up, now.” Why did I hear trumpets whenever I was asked to part my legs?

“It’s just a massage,” he said. “Very popular.”

The machine began to buzz rather unnaturally. “A little bit more,” he said. I dropped knees further apart. “Okay, now relax. I think you’ll like this, Kate. 4000 pulses—but it should be plenty.” He touched the fork to my childbearing place, and although the first instant alarmed me almost to shrieks, the treatment was rivotingly pleasant.

There were moments when I could imagine everything to be beautiful. Instead of trumpets, for the moment, I heard cellos, meadows, my own breath. The grass lying down for a breeze, the rick-rack call of the Cattle Egret. The squeaky Northern Flicker.

My head cleared and cleared, the way it will in a meadow, and within maybe fifteen or twenty seconds, everything painful burst away. It reminded me, actually, of a sensation I had experienced after Pat’s birth. Between agonies. The sensation that, at the time, I had wanted to connect with her, and with love. Could I love the toaster? I could still feel the hum—pleasure, musical, transferred.

By the time I opened my eyes (for I had been closing my eyes) Dr. Duggan had already unplugged the appliance and toted it back to the cupboards, where he rested it on the counter, beside the sink. “What you just felt,” he began, “was what we doctors call a ‘hysterical paroxysm.’ There are a few side effects: disturbed breathing, muscle contractions, slight discharge. But you feel better, no? Let’s repeat the treatment, say, once each month until I’m certain you’re out of danger’s reach. Danger’s reach? I mean harm’s way. Kate my dear, I’m getting old.”

I glided outside and began my two-mile walk home through the desert. I questioned myself: Do you still believe you’ll die when Pat’s thirteen years old? Do you truly believe God has spoken to you? Yes. I would die. But it didn’t matter: I felt brighter than the April sun—powerful—for having had my revelation, for being labeled a hysteric, for finding something in the gynecologist’s office that Bill could not touch.

By summer I had taken to seeing Dr. Duggan twice a week. The doctor encouraged me, feeling the frequent sessions might actually accelerate my progress. Bill took to complaining that paying for all these office visits was drying up our account.

“I want to save for a sewing machine,” he claimed.

“Why?” little Bill, Jr., just three and half, asked.

“Why?” Thomas echoed, born two years ago February. I always gave birth in winter.

“I like to sew but the needles are too small for my hands,” Bill answered. Turning to me he said, “You should be pleased to have a husband so eager to take some of the needlework off your hands.”

“I won’t compromise my recovery.” It was no use mentioning I still believed my revelation; he didn’t even know I’d had one.

“You’re fine,” he said.

“I’m hysteric,” I responded.

Then little Bill laughed, because he always laughed when we said things he didn’t understand, and Thomas laughed at little Bill.

“And stubborn,” Bill said, joining in their laughter.

One happy day, about eight months after my initial consultation, I was scanning the bib patterns in Needlepoint when I came across an ad for the Chattanooga: with its “multi-cantilevered design, you will become your own fountain of youth with the Chattanooga. Setting the standards for home-use vibrators.” It was far too expensive at $200—not to mention intimidating in bulk and quantity of appendages—but in the back pages of the magazine I found the far more humble Jasper; at just $5.65, “even your doctor’s wife will want one!” It showed a tiny picture of a euphoric woman holding something—presumably the Jasper—against her abdomen. It could be in my home within four short weeks. I sent Dr. Derrio & Co. the cost plus shipping from some money my parents had given me the day before my wedding that I had folded into a package of Hartmann’s ladies’ bandages, knowing full-well Bill kept away from products of this nature. I wanted my Jasper to be something Bill kept away from as well.

The most frightening day of my life—more so, in some ways, than the day I realized I would not live to see my daughter reach womanhood—was the day the Jasper arrived. Thankfully, Bill was out at the mines working an extra shift, and as soon as I had tucked up Pat, Bill, Jr., and Thomas, for their afternoon naps, I sat on my bed, cut open the box, dug through the pink packing tissue, and held the Jasper in my hands for the first time.

It was untastefully gold—fool’s gold, Bill would probably have called it. I called it the gold of gun grips and whiskey labels. Guilt-gold. Other than that it pretty much looked like an electric iron, and weighed at least as much. Maybe I was being too harsh—deliberately searching for faults so as to permit myself to continue seeing Dr. Duggan every week: Now I would have no reason to leave the children with Alma, to name the birds I happened across along the way to the doctor’s office, to name the birds out his window. I glared out my own window at Bill’s shed, inches from the pane.

There were no instructions but it didn’t take a train engineer to figure it out. I plugged it in, held the machine firmly by its handle, and flipped the switch. It buzzed and trembled before me. I felt strangely masculine, sizing it up. A man evaluating his new wife. I liked the feeling. I lifted my skirts and pressed the flat of it against the doorway to my womb.

And then, almost immediately, my water broke. My first thought was that I was about to give birth to yet another of God’s creations. My second, that I wasn’t pregnant. I had read the warning printed casually on a thin card tucked into the bottom of the packaging: Paroxysm experienced variously by each woman. Variously? Did that mean some of us became instantly pregnant? I ran to the doctor’s in a fit of horror.

“It came back!” I cried, bursting in an another woman’s appointment, squeezing his cold hands. “Doctor! The hysteria came back!”

“Katie! What happened?”

I described the recent events as I they had come together in my head as I ran: “A real vision! I saw it. I’m going to have another baby. But I won’t. I’ll become pregnant again, but the baby won’t live. It will die in a puddle on my bed!” I fell to my knees. He pulled me up and led me out to the hallway.

“Katie, why would this happen?”

“I’ve angered God.”

“God!”

I confessed about the Jasper.

“Good God is that all?” he asked. “You’re not pregnant, my dear! And you’re not going to have a miscarriage! You simply had an ejaculatory response. It’s completely normal.” He hugged me. “Oh you poor dear. I should have explained earlier.”

“Doctor,” I whispered, unconsoled, “I think what I was … doing … I think the church may consider it masturbation.”

“Don’t be silly,” he said, smiling. “You did nothing I haven’t done for you dozens of times.”

“Yes, but … when a doctor does it it’s not a sin,” I said.

He reflected a moment, then held both my shoulders in his crackly hands and looked me in the eyes, as if he knew me well. “We’re all kidding ourselves a bit here, aren’t we, Katie?”

“What?”

“We act a little more innocent than we actually are. Just because we call it a ‘hysterical paroxysm’ or an ‘ejaculatory response’ doesn’t change what it is, now does it? Queen Victoria is dead, after all; we may as well admit it.”

“Admit what?”

“Katie, you can’t tell me you didn’t know all along.”

“But when a doctor—and when I did it to myself—”

“That’s right, dear.”

And I knew, as I had known all along: “It’s the same.”

He dropped his hands from my shoulders and patted my hands. “I’ve never been able to live my life in full accordance with the Christian principles. I do my best, but when it comes to letting a patient suffer for naught, for no other reason than—if I may be so bold—dissatisfaction in her marital relations, which in my opinion is at least half the cause of this so-called ‘hysteria’ … when I know the cure is so simple and effective and hurts no one, well, I can’t in good conscience advise her to drink some ridiculous tea—or else go home and expect her husband to something about it.”

I leaned against the wall and pushed my palms against my forehead. “I’m so ashamed.”

“Katie,” he began, patting my arm, “you have nothing to feel guilty about. I think you’re a wonderful woman.”

The door to the examining room opened and Alma stepped out. “Kate, I thought that was you. Whatever’s the matter?”

“Alma,” Dr. Duggan said, “you and I were nearly done anyhow; why don’t you walk Mrs. Ryan home?” With one hand on the wall, he shuffled back into the room, chuckling to himself and closing the door behind him.

Alma and I went out into the desert, where it was cold. January. The sinking heart of winter.

“What has Bill done this time?” Alma asked. “And what’s this about a miscarriage, a prophecy?”

“Nothing really.”

“It’s never anything, really. You should talk to people, Kate. You never tell anyone what you’re thinking.”

“No, really, it’s nothing. I’m feeling better.”

“Well, whatever it is, Bill’s a good soul, a real angel. Speaking of angels, have you heard about the new electric dishwasher? I ordered one just yesterday from Sears, Roebuck.”

I didn’t respond. We walked a stretch in silence until we heard the clattery sound of a Cinnamon Teal out near Willow Creek.

“They sound like teeth chattering, don’t they?” Alma shuddered.

“They sound beautiful,” I said.

Beauty’s a chatter, a hum, an old man’s voice. A Flicker, a Jasper, a child.

They pulled her from me, both of us screaming, late on March 16th, although Bill insisted she was a St. Paddy’s Day baby. Why insist otherwise? It made him so happy. “I work all night in the copper, but I come home to a pot a gold,” he’d said the next morning.

I had my revelation after lunch—lying in bed, recovering, holding with my right arm my ugly but already elegant newborn, touching myself quite sinfully with the middle finger of my left, imagining a humming-bird’s wing, beating, furious, suspended in the open sky—when my husband walked in. “… the field until nineteen-twenty … — … five,” he said and although he stopped short, I knew that just as he had chosen the date of Pat’s birth, he had chosen the year of my death. It wasn’t really a vision so much as recognition of a divine tonality, the click-cluck-click-cluck of the “nineteen-twenty,” the steep drop of the “five.” I knew it as readily as the call of a Wood Duck: God had witnessed, and had sent Bill to impart my fragmented sentence.

“I would have done that,” he said, staring at my left hand, “if I had known you were a whore.”

But today, walking with Alma, when I listened now in my head to the memory of Bill’s words, as I went up and down the intonation, I realized that while his first statement possessed the plummet of prophecy, the second did not. I was not a whore. I looked forward to going home, putting the Jasper in plain sight on the kitchen table, and saying something back to him. I had a retort. And it had nothing to do with shame. I might die but I had thirteen years to make him listen.

“My children!” I remembered, “I left them alone!”

“Run!” Alma said.

I took off toward the house, my skirts blowing up in the wind and the meadow hard and bumpy as frozen lemons beneath me. I chuckled, thinking how it would all look in a few months.