Standing Out: Eastie friars stay traditional

East Boston's Franciscan Friars show the neighborhood how to do traditional community

By Brooklynne Kelly Peters

4/30/10

Living a day without a computer, television or phone might sound medieval, but to East Boston's Franciscan Friars of the Primitive Observance, that might just describe a Tuesday. In an age where the Internet connects people through social networking sites and virtual communities, the friars are abandoning technology and going back to the basics.

The five Franciscans of Primitive Observance who live on Paris Street in East Boston are very hard to find. They're not listed in the phone book and they can't be contacted through email. But this doesn't mean they're not connected. On the contrary, they're on a first-name basis with everyone in their neighborhood.

"Basically, our way of life makes us connect with people," said Friar Pio Anthony "because we have to sort of do that to survive."

One of the four vows that the friars take is the vow of extreme poverty, which means that they literally own nothing, and survive entirely off of donations. Brother Pio is the designated "Quester" for the group who goes door to door begging for "food for the love of God."

They don't use money; they don't have checkbooks or bank accounts. They don't own their apartment, a car, a computer, a television, or even a microwave.

"We're pretty much off the grid," said Friar Andrew Beauregard. "It's this radical lifestyle that's totally shocking to anyone who'd hear about it."

The friars take their cues from St. Francis of Assisi, an Italian Catholic saint who lived in the 13th century. St. Francis felt the need to imitate Jesus in a radical way by giving up all of his earthly belongings to the poor. He started a movement and within 10 years, he had 5,000 followers.

"And he did this without TV or Internet or advertising," said Father Andrew.

Brother Pio and Father Andrew belong to this small division of 12 Franciscan Friars who are split between East Boston and Lawrence, Mass. and who have taken on the extra vow of extreme poverty, The group is small on purpose. They keep their numbers down so that they can maintain their desired level of poverty. The five in East Boston live in a small three-bedroom apartment, using bed sheets as makeshift walls. Father Andrew compared the size of his room to the size of a picnic table .

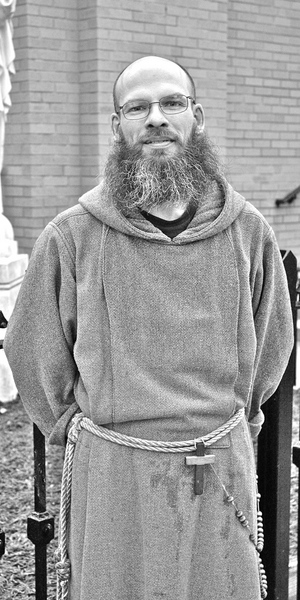

But their lifestyle isn't the only thing that sets them apart. The friars also get a lot of attention for their attire. Their uniform is a gray sackcloth habit with a rope tied around the waist (knots in the rope represent their four vows: poverty, chastity, obedience, and total consecration to Mary). They shave their heads to protect against vanity and let their beards grow to promote austerity.

Both Brother Pio and Father Andrew were raised in the Catholic Church, though neither was ever pushed toward the life they chose. Father Andrew remembers the seed was planted in him early when he read the illustrated Bible in second grade.

"It just made sense to me to imitate Jesus in some way, to give my life to him," Father Andrew said. "[So much as] a seven-year-old can do that."

Brother Pio took a more winding road before ending up at the priesthood. Though raised Catholic, he said he left the church during high school and lived a wild life in college that got him into some trouble. After a long night of drinking, he got involved in a car chase that ended up with four demolished parked cars.

"I cried out to God because I was so lost, you know," Brother Pio said. "And [I really felt] God's embrace come upon me."

Brother Pio and Father Andrew joined the priesthood around the same time in 2001. They began their religious life on September 8, 2001, and were met immediately with the tragedy of 9/11. They used the event as an example of why they choose their way of life.

"I never saw the twin towers fall," Father Andrew said. "To this day... I haven't. I know that they fell. I know that September 11th happened. People came into our friary saying, you know, 'They're bombing everywhere! We're under attack!' And what was our response? We didn't go out running to the TV, glued to the television sets, watching the twin towers rise and fall a hundred times on television, having our psyche destroyed, which is what the enemy wanted to happen. We went right to the chapel and spent the whole afternoon in prayer. Because at that point, what can you do other than pray?"

And this is their calling, Father Andrew said. They said they choose to respond to the needs of the world instead of sitting in front of the television worrying about things. The friars do this by helping the poor, hosting youth retreats, holding food drives, helping out in soup kitchens, and by offering a listening ear for neighbors in need.

Father Andrew explained that while many people think that being extremely technologically savvy makes them more socially connected, it's often the opposite. He described conversations he has with his younger brother, who is an avid online gamer. Father Andrew spends one week a year with his family, and he spends that time talking to the back of his brother's head while his brother plays video games.

"[He's playing against] someone that he's never met before and never will, and it gives you the impression that he's actually communicating with someone, and there's a form of communication taking place. [But] where's the intimacy...there? I see that that's lost. I see it in other people, too. Things like television...computers - it zaps children of imagination, of the ability to think for themselves sometimes, and many people just become shells, really."

But while the friars view their way of life overall as extremely rewarding in most ways (the economic downturn didn't affect them at all), they admit that they sometimes miss modern conveniences.

"There are times," said Brother Pio, "you want to tell people something and you can't do it quickly, not having a phone."

Father Andrew recalled a three-week road trip where he hitchhiked from Maryland to a Franciscan home in Argentina.

"There are times along the hitch when you kind of...wish you might have had a cell phone where you could call someone to say, 'Pick me up 'cause I'm in the middle of nowhere...'"

Brother Pio said he sometimes wishes they could be in contact with more people than they are. "There's nothing intrinsically wrong with technology. Other Franciscan brothers are...doing wonderful things with it."

But in the end, they have no doubts about the life they've chosen.

"There's a place in the church," Brother Pio said, "or rather, a need, [for] what we're doing."

"Basically, our way of life makes us connect with people," said Friar Pio Anthony "because we have to sort of do that to survive."

"Basically, our way of life makes us connect with people," said Friar Pio Anthony "because we have to sort of do that to survive."